The historical maps of Tainan reveal more than ever a land of freedom. There were still boundaries, like the natural canal formed between solid island brim and soft, ambiguous sandbar, or the former Tainan castle wall. No matter how they are—absolute, intimate, powerful, everchanging—some kind of freedom was left between. People found their own way of living, not only with other people but with nature, the terrain and the tide. There were routes stretches freely to its own ends, and the informal grids organically formed by adjoining farms or oyster ponds. The shifting of density informed communities, while voids are left for imagination. Rolling mountain hardly blocked, and the living condition was bound to the ground—the ground by which people go the way it goes, rugged or flat or undulating.

That was all before the grids of urban planning had ever begun to take dominance over the entire land. From there on in, everything is planned and restricted. From street to alleys, sidewalks to blocks to communities, every piece of land seen was filled with strategies and tactics, guided by a certain group of people how this entire region will look like—from the top at least. Roundabouts and orthogonal grids collided, in a somehow awkward way. Remnants of freedom curled within the frame enforced—so do the inhabitants. And, as it turns out, this dense exploiting doesn’t actually offer much space—not only in terms of the number itself but that for decision and freewill.

Putting together these maps, they raise question and somehow offer directions at the meantime. The question is raised, if read in chronicle order, as: “where goes the land of freedom, and how can it be re-imagined in the future?”. The graph after the last one is still waiting to be unveiled, on which the living condition could be new or known. And, the direction offered, if read inversely to the chronicle order, propelling us to find ways back in the primitive conditions, in which freedom exists under amorphous sprawling of the land, the water and their dwellers. We are just part of it, so do our architectures and built environments.

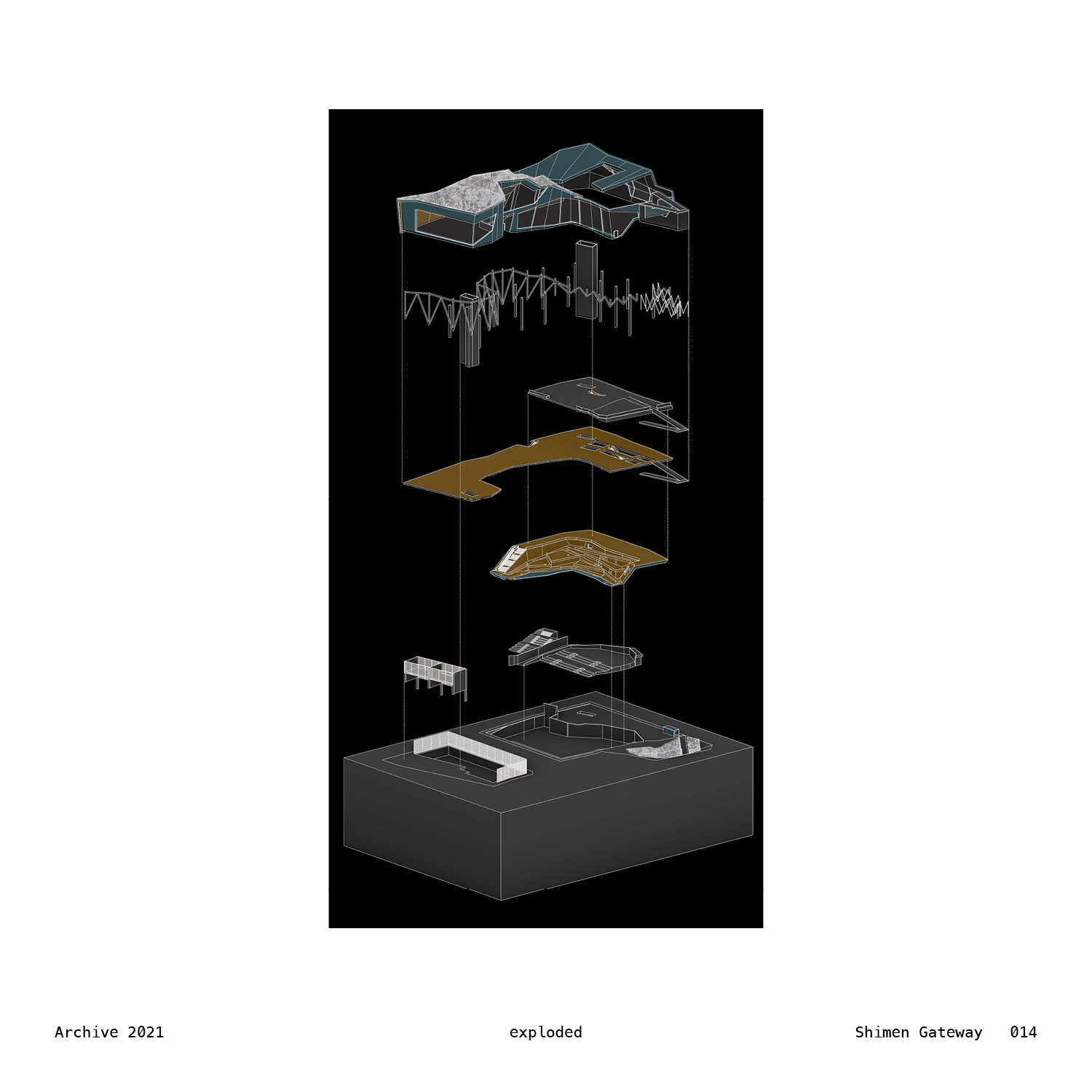

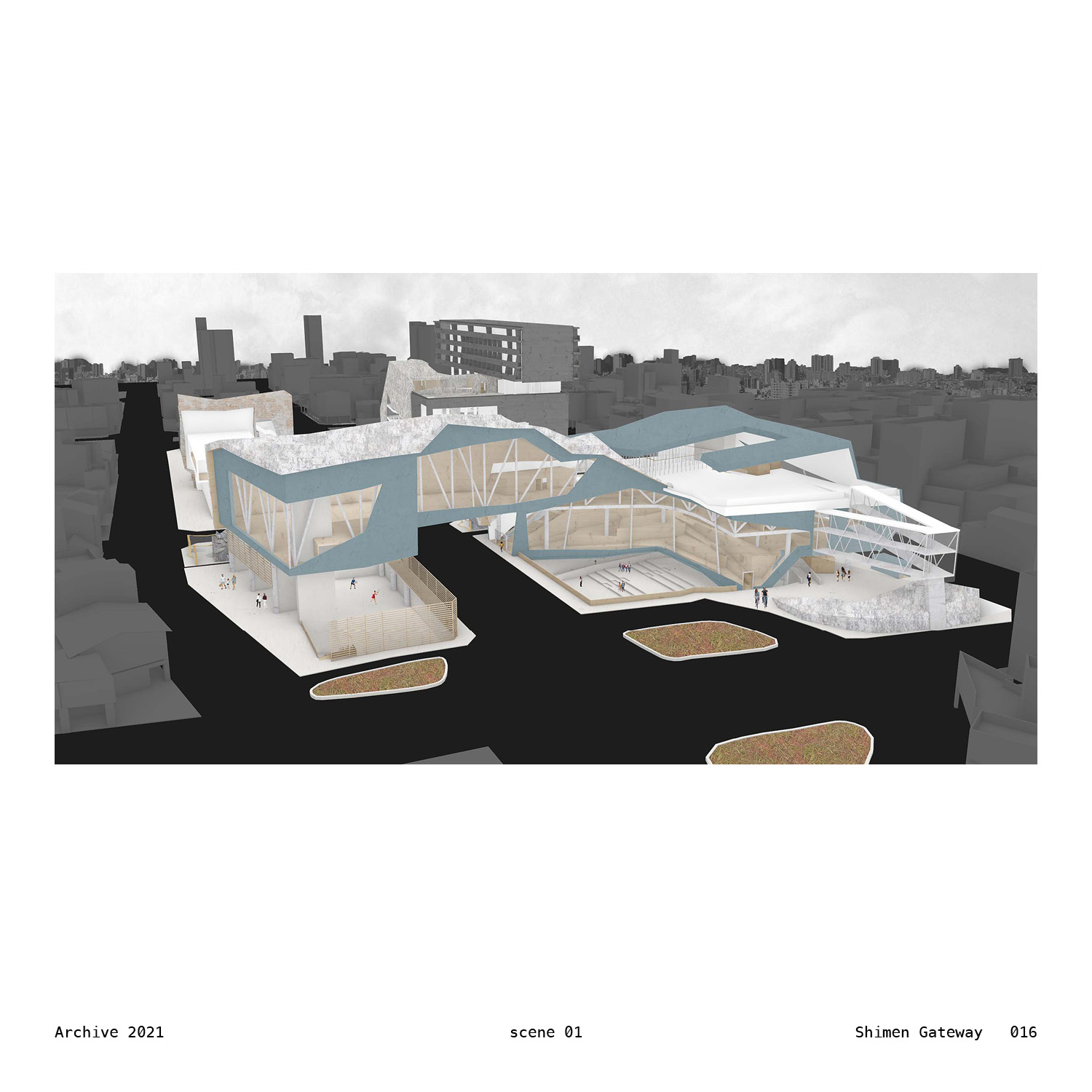

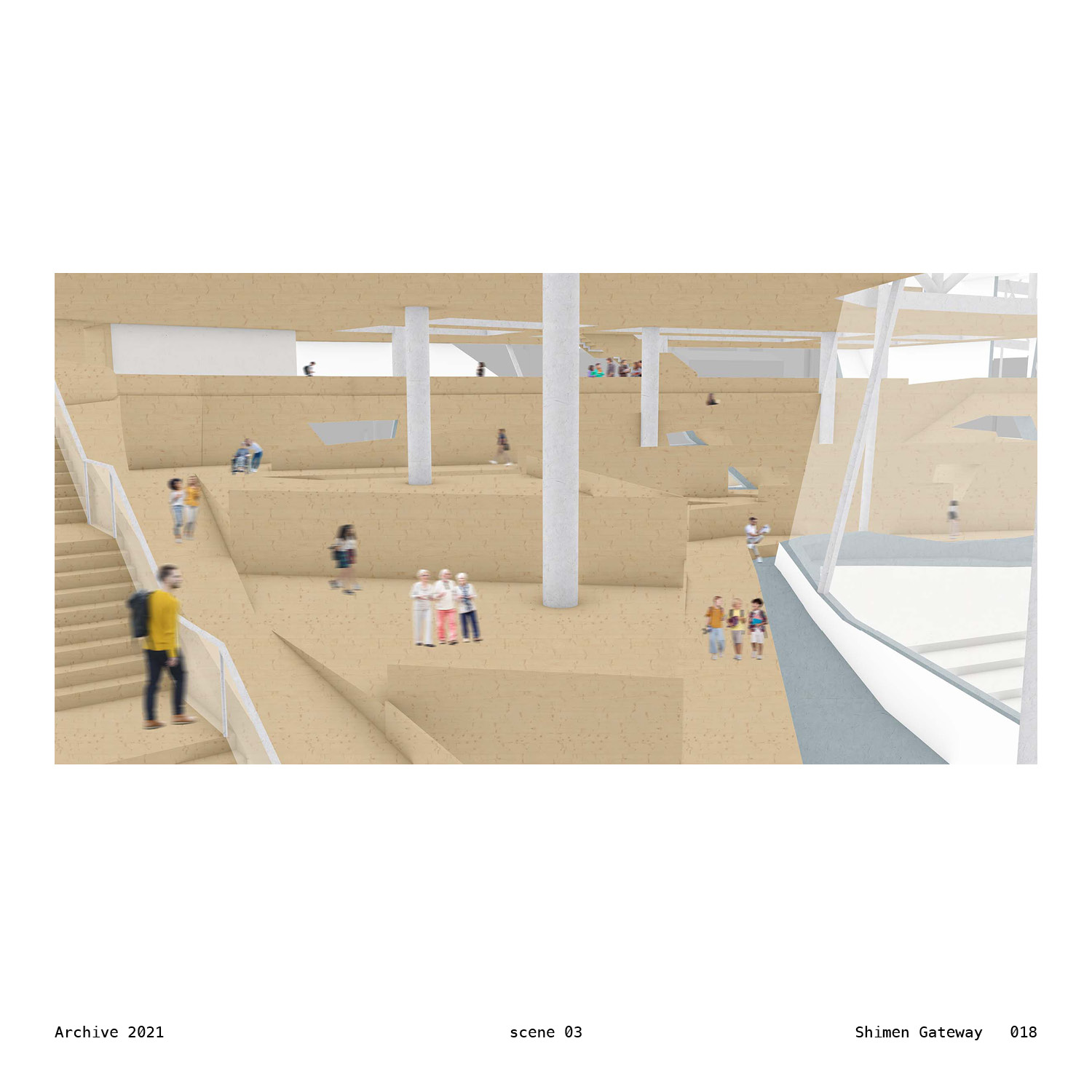

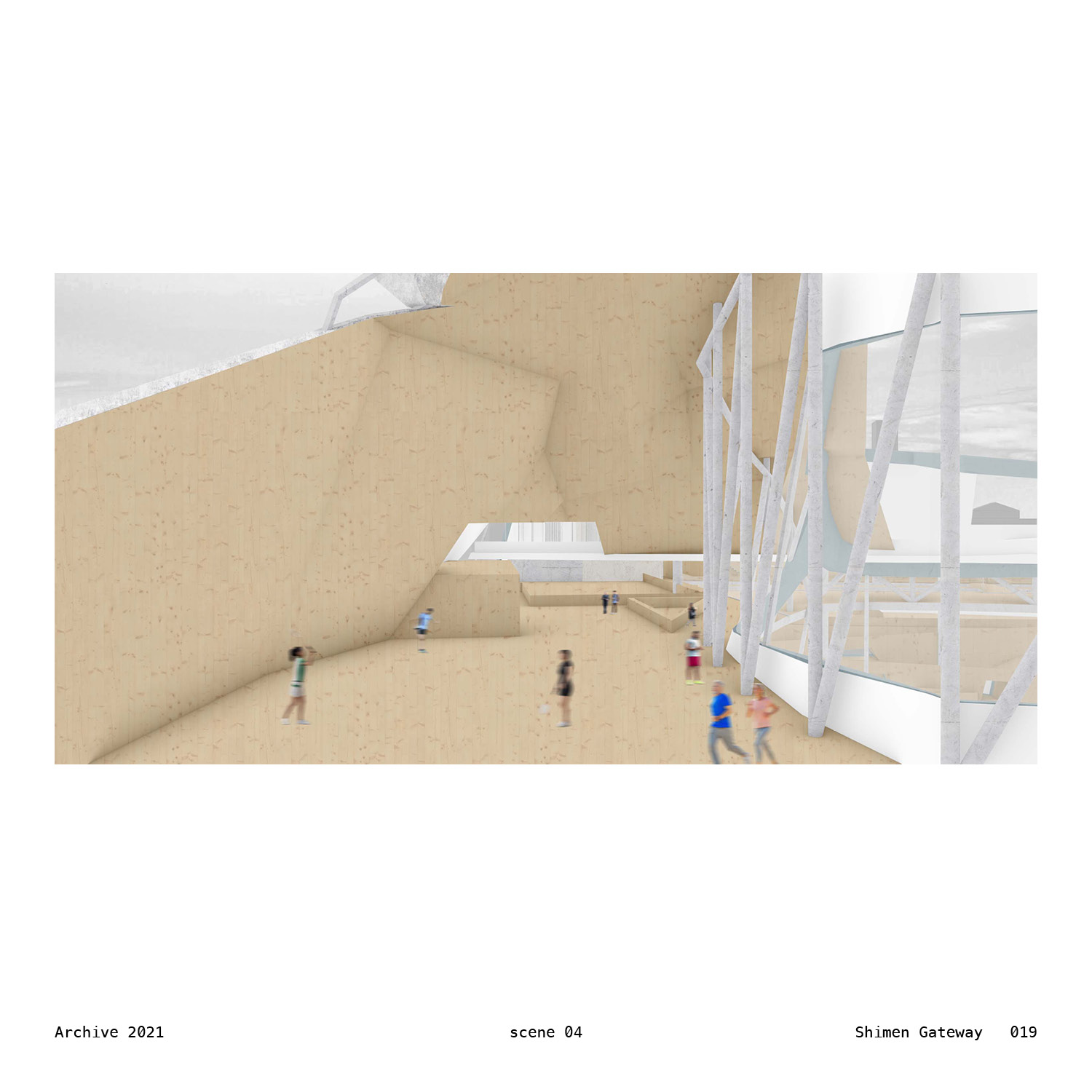

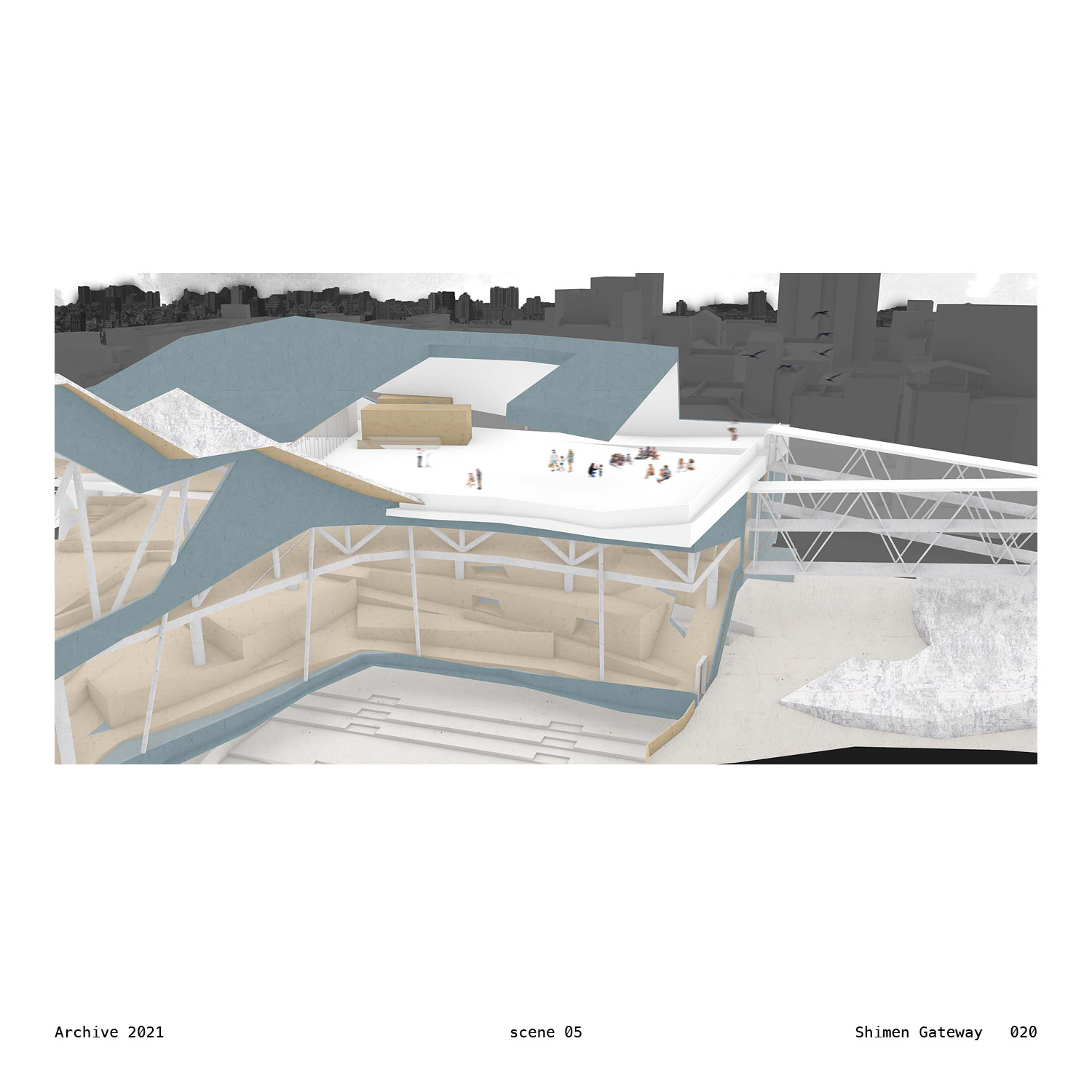

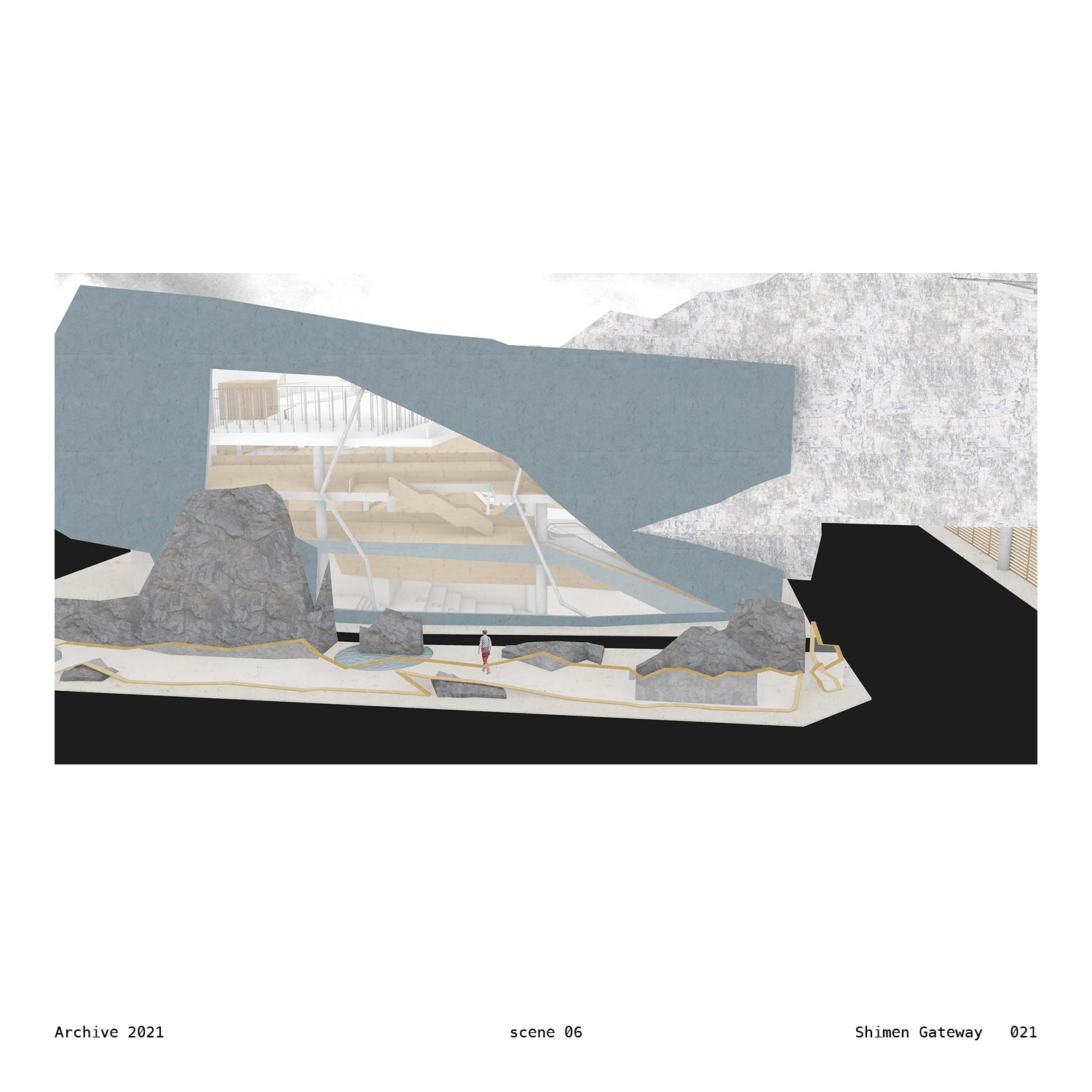

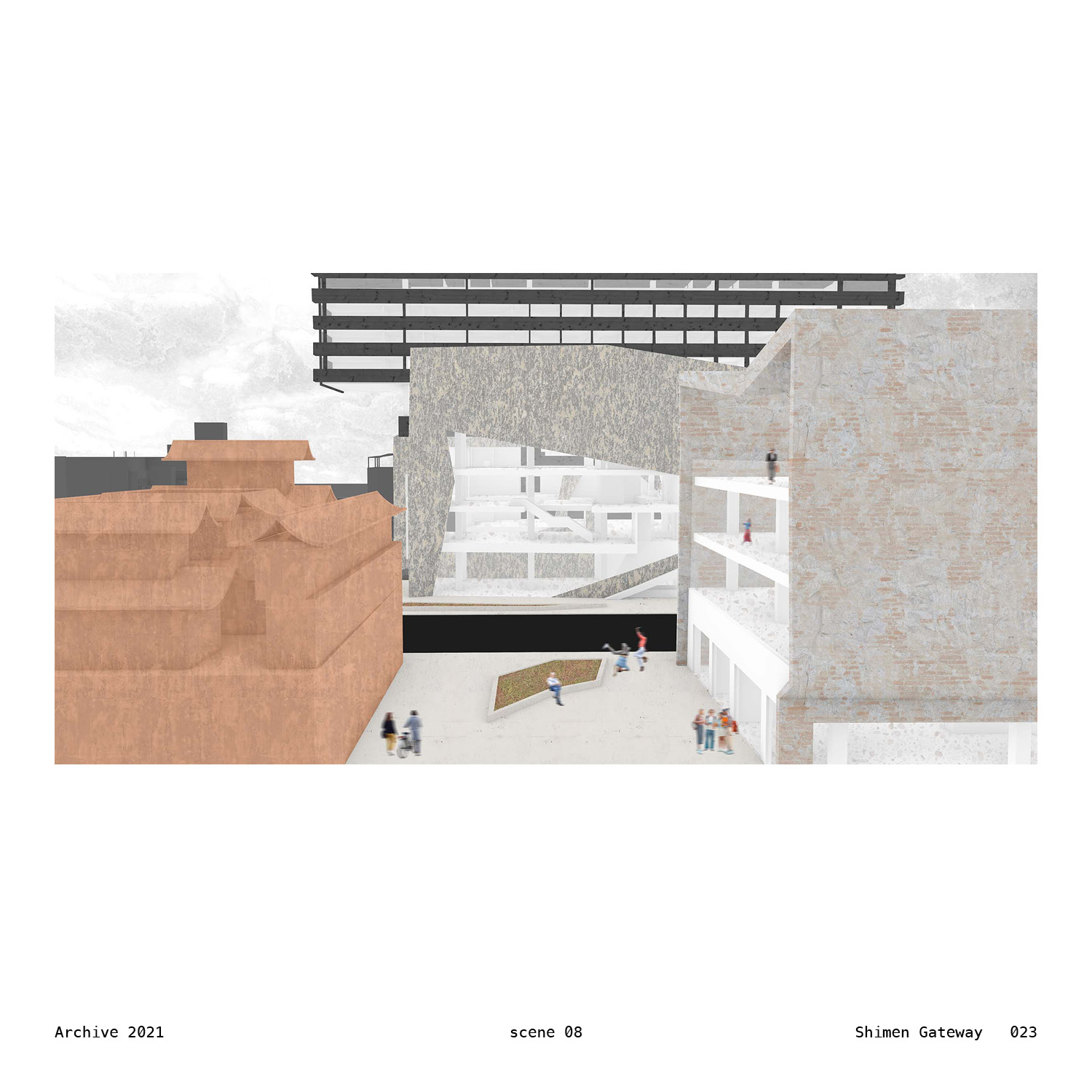

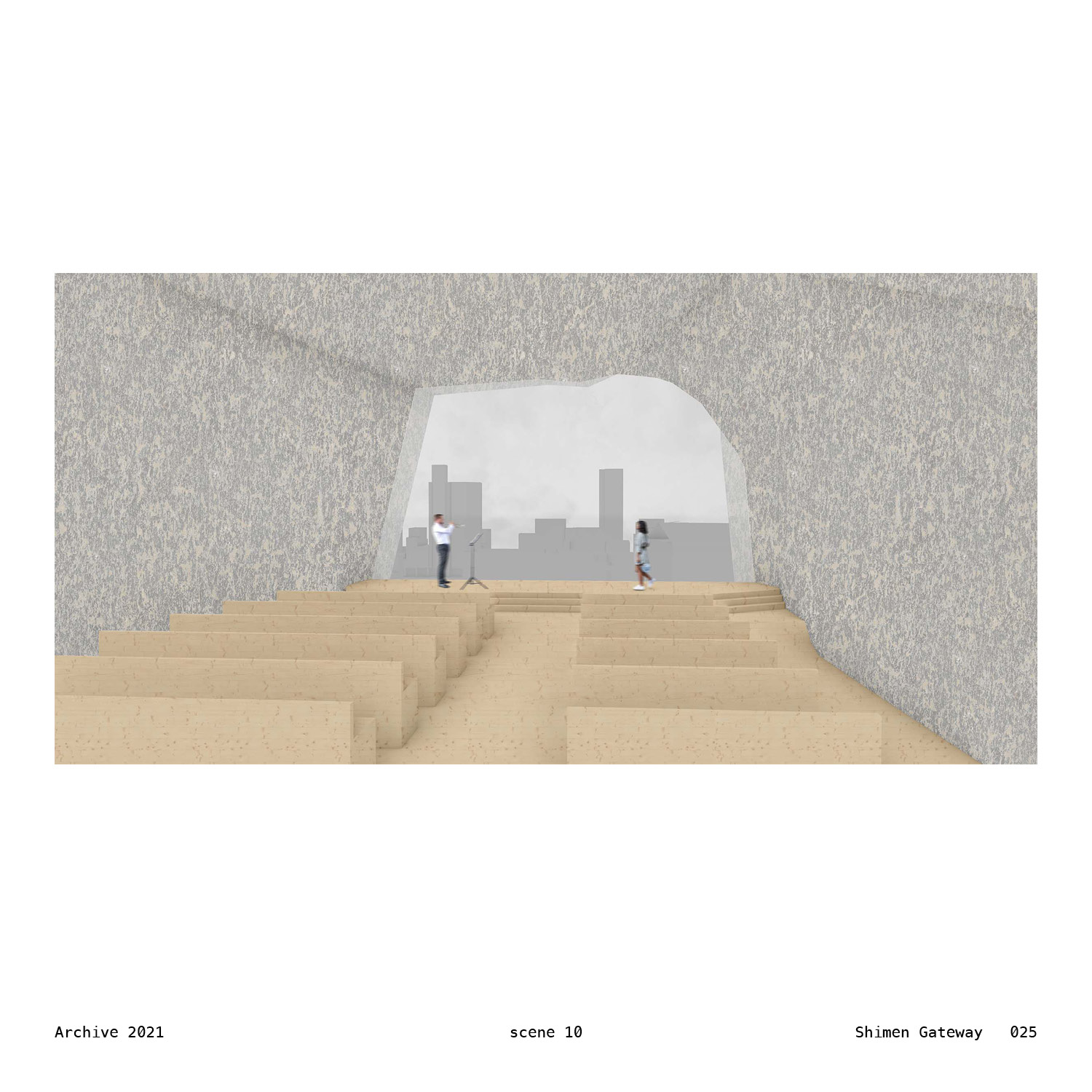

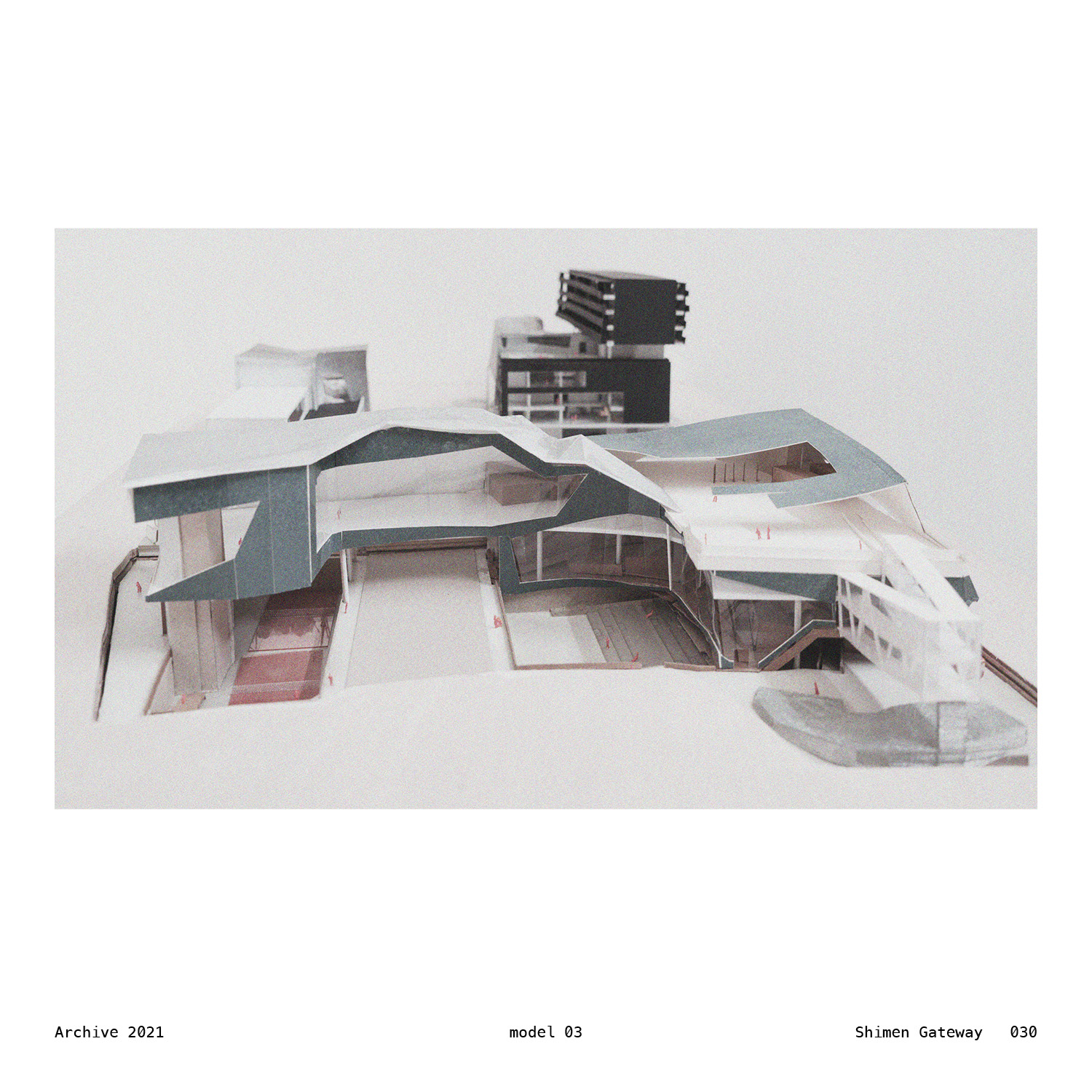

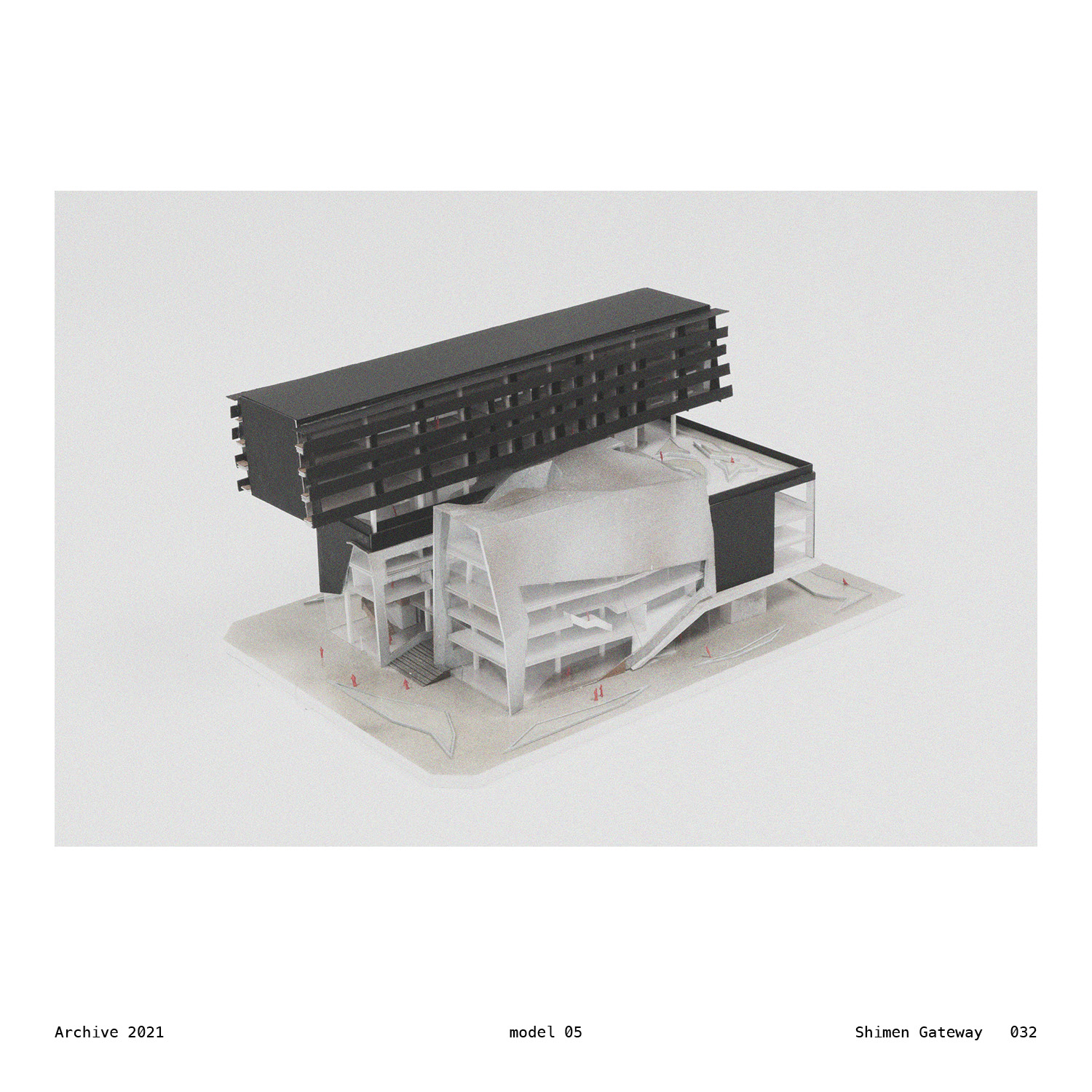

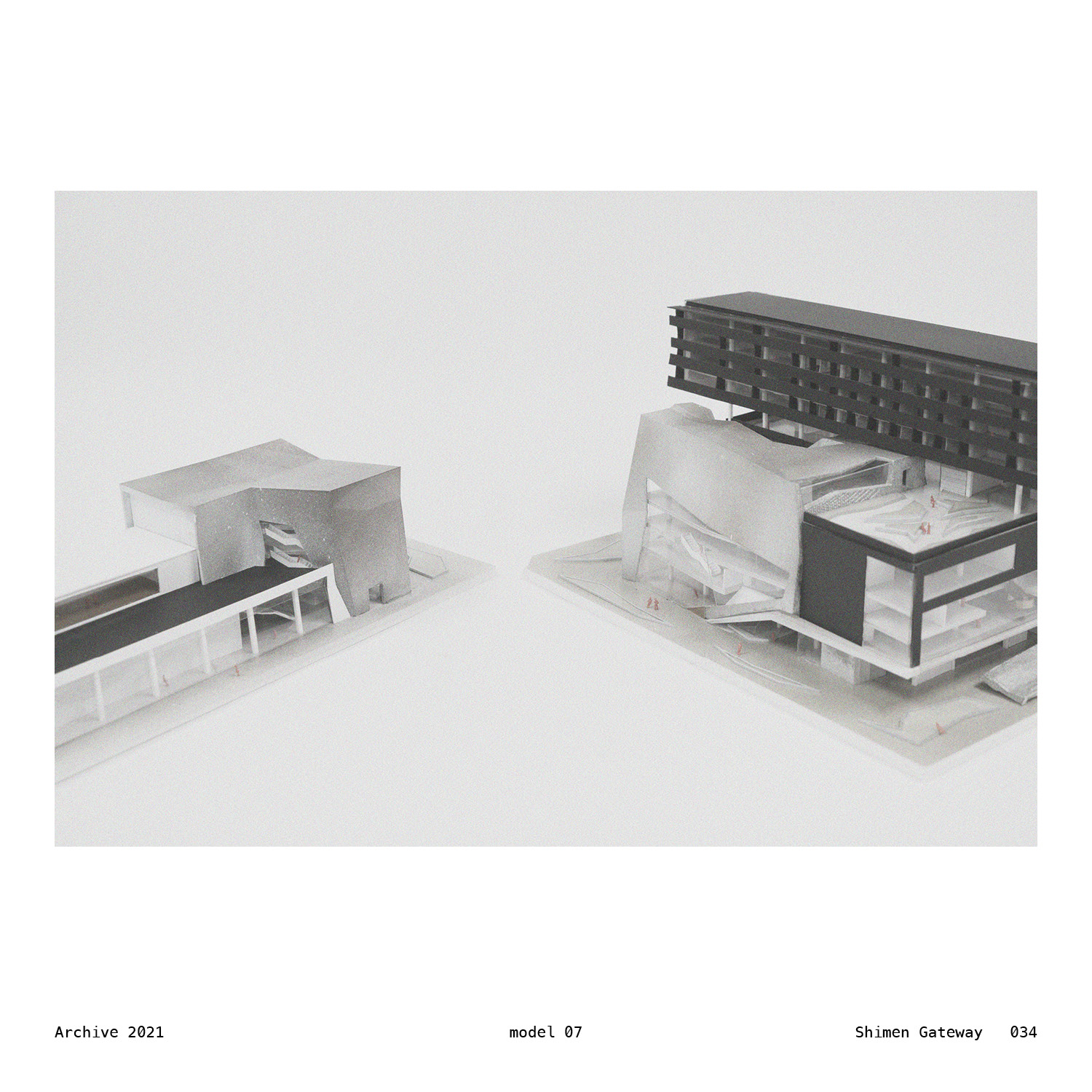

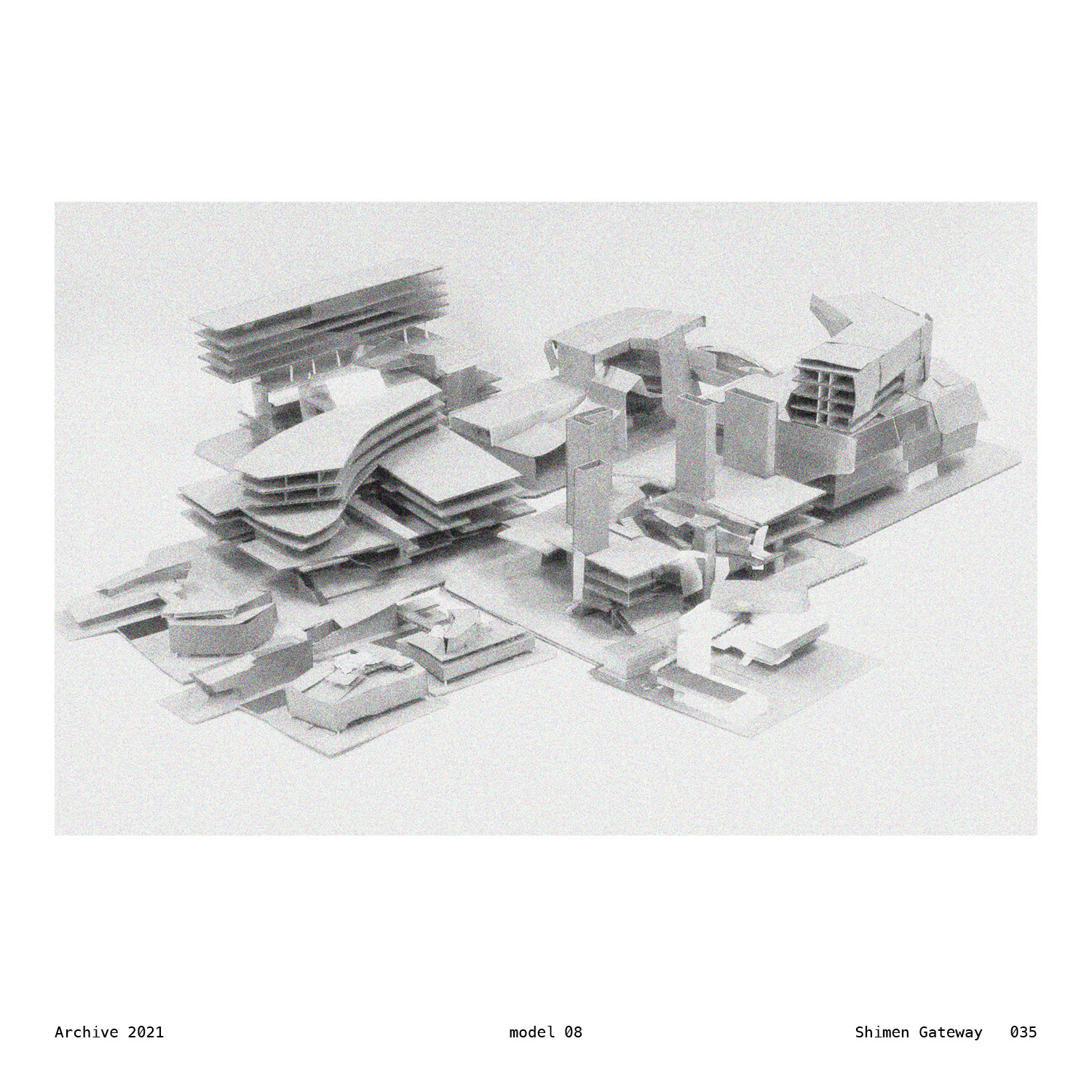

These architectural projects proposed on the consecutive blocks flanking Fuqian Road in the city of Tainan look into the possibility of architecture not just as bland, solid objects—but as part of the landscape, or amplifying the landscape, or even create a kind of landscape itself. These manmade structures resonate that of the land, by its form and its relationship with people.

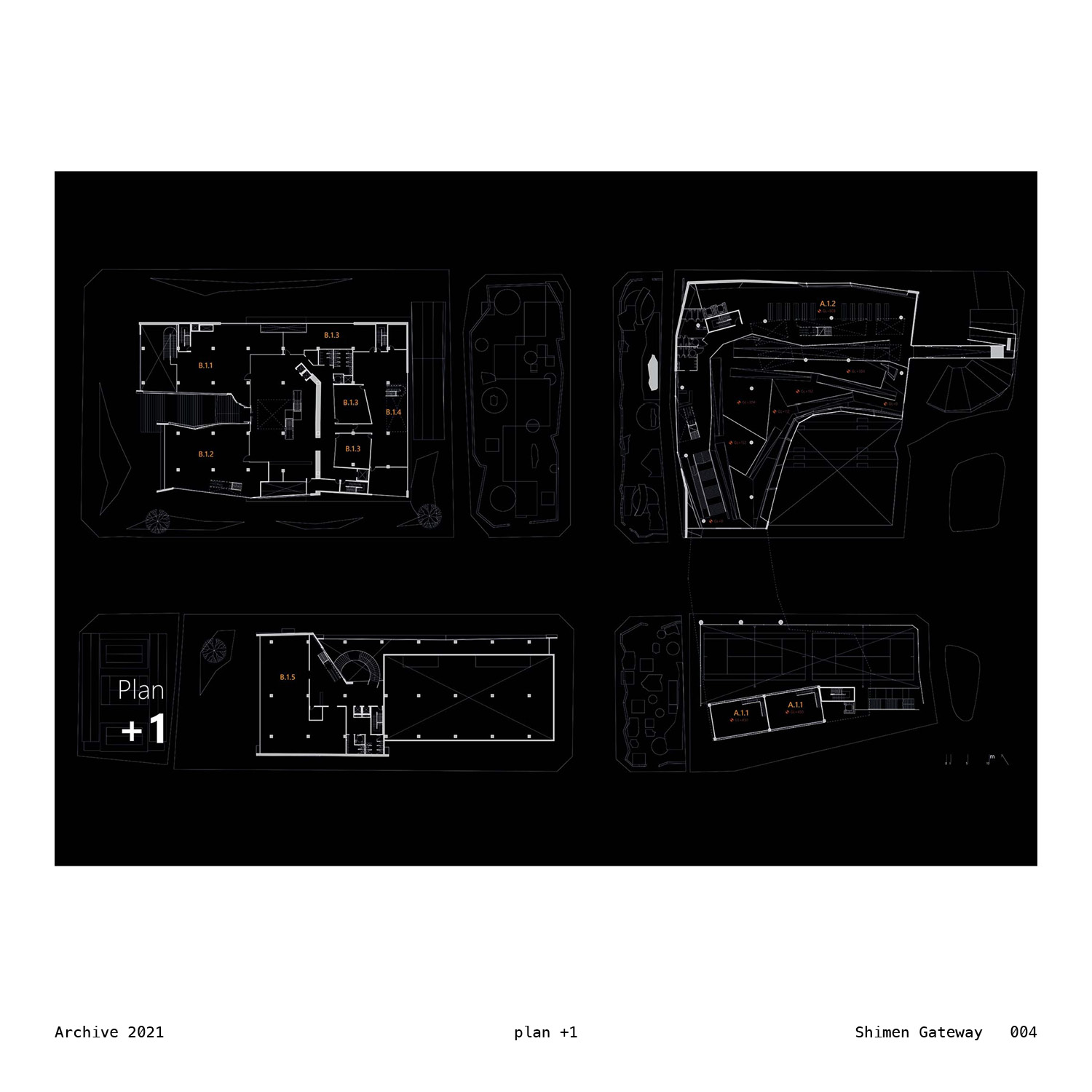

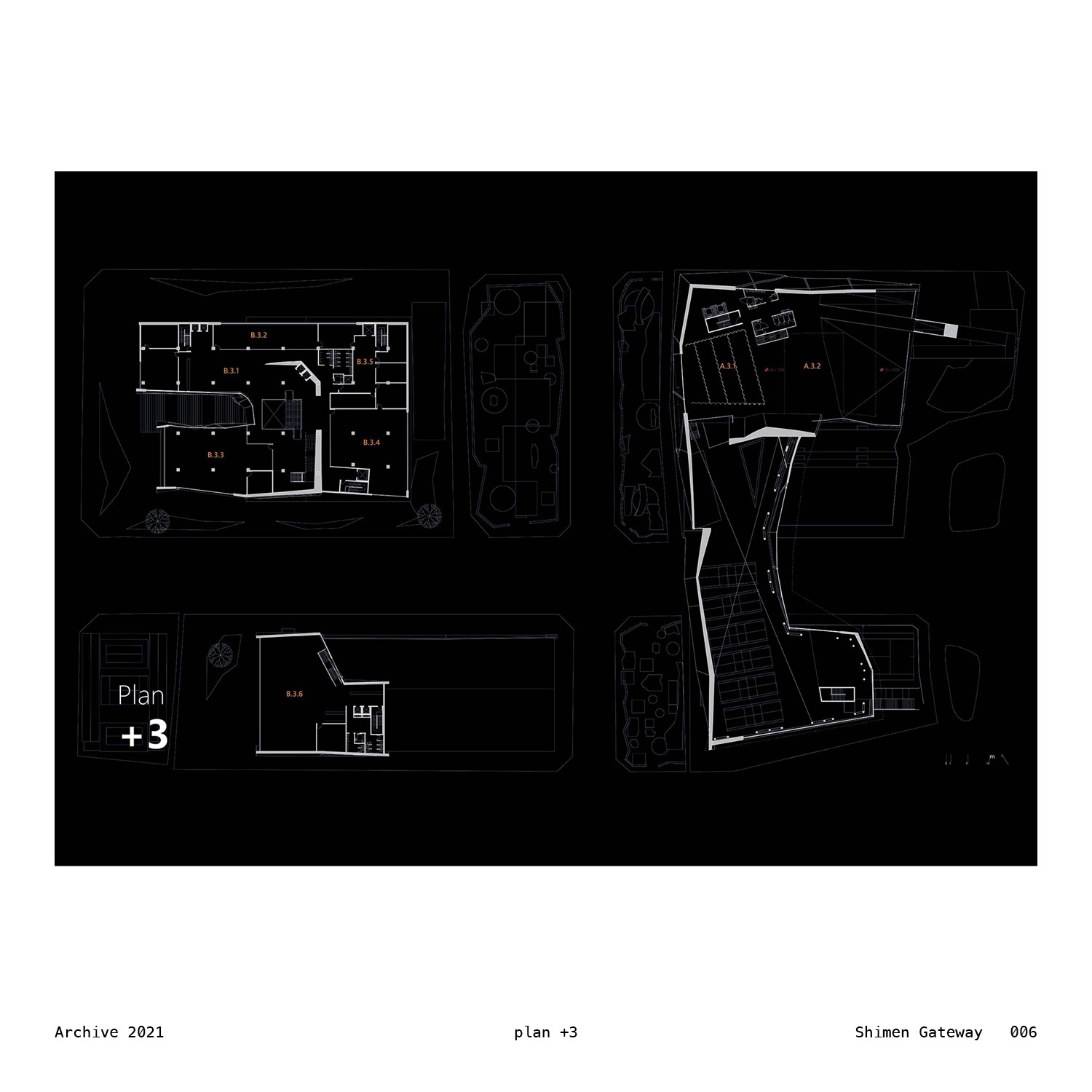

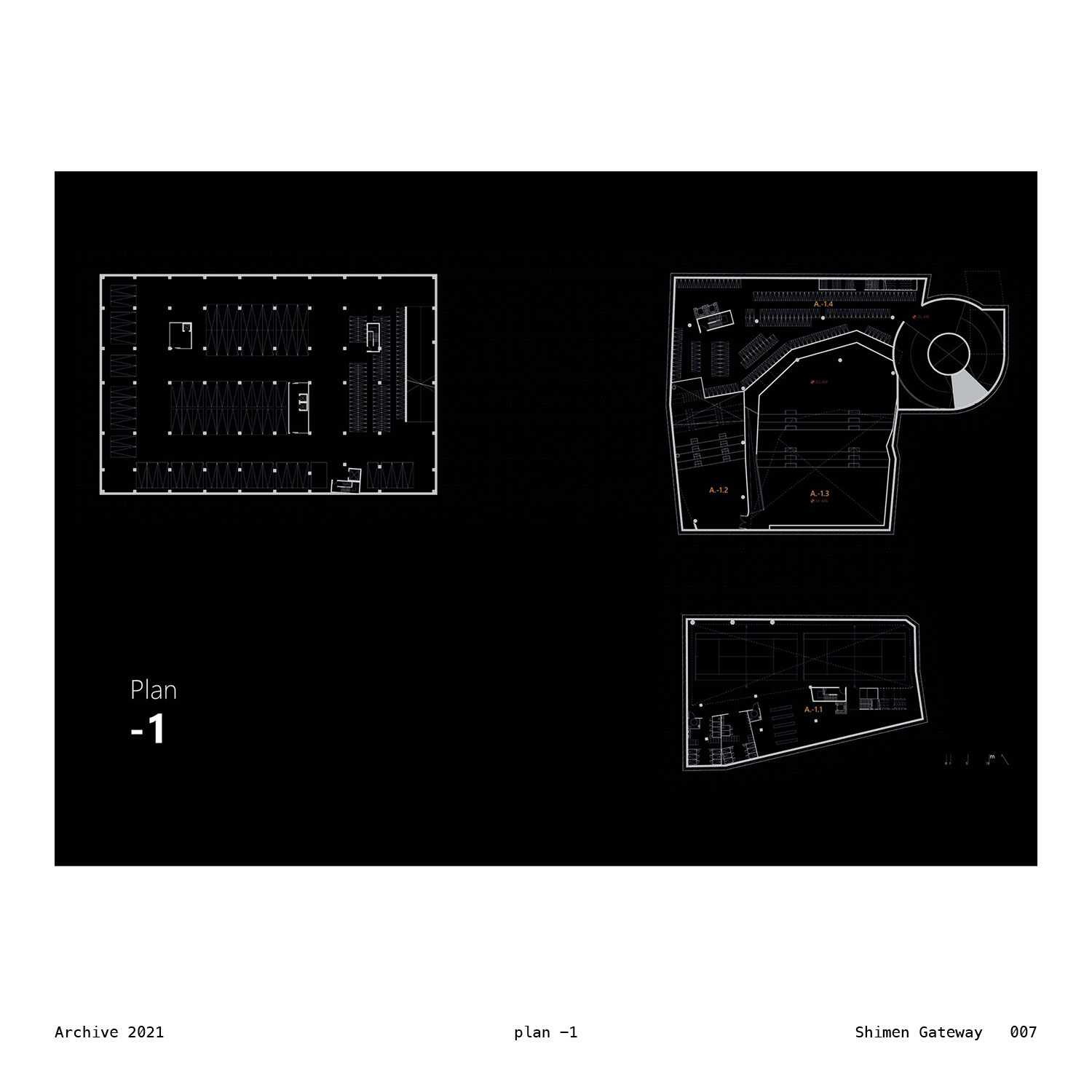

At the eastern part of the plan is a new community center dedicated to the residents within the surrounding six villages. In the central three blocks between, a garden is inserted. In the west, two structures on the opposite sides of Fuqian road houses the Taiwan Design Research Institute (TDRI) southern branch and the KINJO plaza, respectively. TDRI is a government operated organization in charge of various design events and projects all across the nation. KINJO, on the other hand, is a Taiwanese accessory manufacturer that features wedding rings and artistic, limited braces by top-notch craftsman.

These together, could be seen as different means of exploring and rethinking architecture in the names of landscape. There is a kind of rolling hill extended from the ground and expand into, flow all the way up till the top of the structure. There is mountain and water and stones and forest, inherited and interpreted from tradition, either remain in the scale of a garden, or as large as in the form of architecture. The space of freedom is exerted within, and the iridescent culture of our relationship with and our hands for crafting the nature is relayed to crafting the new form of urban streetscape and living environment in the city of Tainan.

Here, between the manmade and the natural, in all forms and definitions of landscape, the interplays are either subtle or dramatic. It’s like the old way it was suggested by the maps, but a new way it is in this contemporary world.